After eight years of renovations, the Waldorf Astoria in New York has reopened and is welcoming new guests. The Waldorf – as most people know it – introduced room service, velvet ropes, red-velvet cake and Thousand Island dressing. It gave its name to a salad, a chain of lunchrooms, as well as a now obscure form of democracy.

In 1907, the novelist Henry James said the Waldorf embodied what he called the “hotel spirit”: it was a place where everyone was equal – as long as they could afford the price of admission. To James, hotels defined America’s emerging culture and ideals. He said this new “spirit” was one of opportunity; of a new elite that was accessible not only by lineage, but by money.

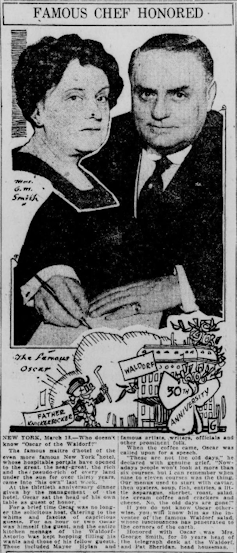

As the historian and journalist David Freeland wrote, the Waldorf generally made room for all who were “able and ready to pay” and who displayed a willingness to “conduct themselves properly”. The Waldorf ethos was developed by its first maître d’, Oscar Tschirky – known simply as “Oscar of the Waldorf” because people struggled to pronounce his name. “Our innovations were startling and sensational”, Tschirky said in his ghost-written autobiography in 1943, “but they were always genteel”.

Those early innovations included the invention of the “presidential suite”, which saw the hotel become an unlikely early force for American feminism when it became a hub of high-level talks between suffragists and President Woodrow Wilson.

Science History Images / Alamy Stock Photo

The Waldorf, then, is an American institution – or, at least, it used to be.

It is now in the hands of Chinese owners and has been shunned by presidents since Barack Obama, worried over potential security risks. The brand itself has been watered down as there are currently 32 “Waldorf Astorias” dotted around the globe.

The story of the Waldorf encapsulates modern America’s crisis of the establishment. Few places better personify the creation of the US version of the establishment (much more about money than breeding or class). And in the past decade, the hotel’s position, like the US establishment more generally, has come under assault by a rival hotel owner, Donald Trump.

The Insights section is committed to high-quality longform journalism. Our editors work with academics from many different backgrounds who are tackling a wide range of societal and scientific challenges.

Trump has his own ideas about how to use these modern palaces to project power – and his innovations are anything but genteel. So what can the beginnings of this former American institution tell us about America today? As a researcher of political and democratic institutions, I have been examining the role of hotels in the story of American democracy. And this particular story begins with a Swiss-born waiter.

Oscar of the Waldorf

Tschirky was born in the Swiss Alpine village of Le Locle in 1866. He and his mother boarded the steamer La France in 1883, bound for New York. In his book, he recalled his mother’s announcement:

Yes, Oscar, we’re going to go to America and live with your brother in that great land of plenty where we can have everything we’ve always wanted.

That night, according to his book, was “the beginning of Oscar’s career as beloved servitor and counsellor to the great and near great of this world”.

Although it would be ten years after arriving in New York, that Tschirky would join the Waldorf (which was just about to open) as maître d’. His contract and salary commenced on January 1 1893, ahead of the grand opening of the Fifth Avenue hotel in March. He would occupy his post for the next half-century as “host to the world”.

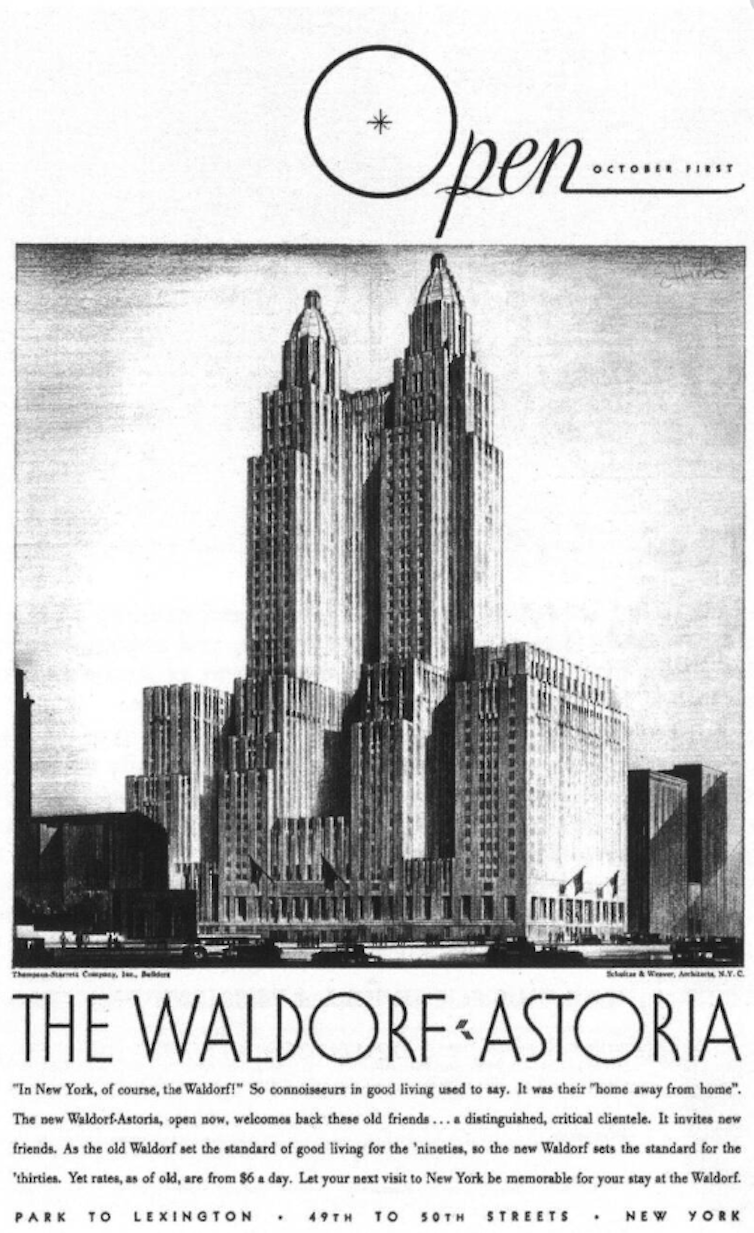

Tschirky would remain in place as the hotel expanded in 1897 when John Jacob Astor IV built and connected the larger, taller Astoria Hotel next door. Then in 1931 the hotel was forced to relocate when its Fifth Avenue location was razed for the Empire State Building. The “new” Waldorf Astoria New York reopened on Park Avenue with the addition of its famous towers, making it the tallest hotel in the world at the time.

AP Photo/Anthony Camerano/Alamy

Tschirky was born just one year after the end of the American Civil War. It was an America of Jim Crow laws and segregation. He would live to see women’s suffrage, but not the civil rights reforms of the mid-1960s.

Read more:

Activists are warning of a return to the Jim Crow era in America. But who or what was Jim Crow?

In this turbulent context, it appears that Tschirky did his best to keep the Waldorf out of politics. He stuck to the advice given by the Waldorf’s manager, George Boldt (himself a German immigrant) who told him that it was “not up to the hotel to settle international affairs”.

Tschirky came to understand, realise, and represent the “hotel spirit” of a new America as he presided over the establishment of hotels as American palaces: not only for visitors, but for the new American aristocracy.

A presidential palace

The Waldorf famously hosted every US president from Grover Cleveland to Franklin Roosevelt. In spring 1897, Cleveland was at the Waldorf with members of his former cabinet, who wanted him as Democratic candidate in the 1900 election. This was the first reported instance of “Waldorf democracy” – in this case, the term was used to identify this new group within (and in some respects differentiate it from) “the democracy”, that was the Democrats.

Shutterstock/Everett Collection

This politics was not embraced by all. As reported in The Ohio Democrat, Congressman Edward W. Carmack of Tennessee dismissed it as “the walled-off Democracy, because they are by themselves, representing nobody, and unable to influence a vote”.

Nevertheless, political elites liked the luxury that the Waldorf offered. Presidential suites were established during Woodrow Wilson’s presidency (1913-21). In the Waldorf, this famous suite emulates the furniture of the White House and still contains several presidential souvenirs, (including John F. Kennedy’s rocking chair).

The hotel was also popular among the famous “Four Hundred of the Gilded Age” – the highest echelons of New York society. The group was originally led by Caroline Schermerhorn Astor. The Astors’ ancestral family home, the town of Walldorf, in western Germany, had even given the hotel its name. According to Tschirky’s book, the Waldorf’s grand ballroom was:

… where Teddy Roosevelt had dined, where presidents McKinley, Taft, Wilson, Harding, Coolidge and Hoover had spoken historic words to the nation, where princes of royal blood had been welcomed, where the great people in every walk of life had been honored.

The Waldorf proved a suitable palace for US presidents and their entourages and Tschirky, a suitable “servant”. When interviewed by Washington DC’s Evening Star, Tschirky “wouldn’t talk about presidents except to say that Franklin D. Roosevelt calls him, ‘my neighbor across the Hudson’”.

adsR / Alamy Stock Photo

But Tschirky, “for all his celebrity acquaintances, never forgot that he was, in the end, a servant”, as Freeland wrote. The Waldorf likewise applied the term to its staff.

Exclusivity, exclusion and ‘democracy’

The world famous hotelier Conrad Hilton, who acquired the Waldorf in 1949, recalled in his autobiography, Be My Guest:

Originally the Waldorf was said to purvey exclusiveness to the exclusive. Later [the writer and artist] Oliver Herford announced that it ‘brought exclusiveness to the masses’. But that exclusiveness remained whether the hotel catered to a convention of three thousand or a tête-à-tête between crowned heads.

The Waldorf ethos projected “taste” and imbued it in others. Tschirky “subtly schooled Americans in fine European dining”. In 1956 – six years after Tschirky’s death – the New York Times recalled that, alongside Boldt, he undertook to teach people how to spend their money. The Waldorf embodied good taste by enforcing it, for example in its expectation of “proper conduct”.

But with exclusivity comes exclusion. Hence, the hotel’s introduction of the velvet rope. According to the Waldorf’s luxury suite specialists, this was done “to create order … the fact that it created a sense of stature and separation was secondary”.

Tschirky’s statement that “all who pay their bills are on an equal footing” reflects one of his “rules for success”:

… be as courteous to the man in a five dollar room as to the occupant of the royal suite. It is an old rule, but it never changes.

We can see from this mindset how the hotel was seen to possess, as American Studies scholar Annabella Fick put it, “a democratic quality … even though it is also elitist. In that, it invokes the democratic understanding of early America, which also differentiated between land-owning gentry and the mob”.

This was not the only differentiation. Just two years after the Waldorf opened, the 1895 New York State Equal Rights Law (commonly known as the Malby Law) – which aimed to abolish racial discrimination in public places – had aroused Boldt’s indignation. According to Freeland, Boldt described the law to reporters as “an outrage, as it prevents us from making any selection of our patrons. A man who runs a first-class hotel must respect the wishes of his guests as to the sort of people that he entertains, and the law should not dictate to him.”

In his paradoxical desire for the freedom to discriminate and persecute as he wished – and on behalf of his customers, real or imagined – Boldt illustrated the exclusion inherent in exclusivity. Boldt’s statement also presaged a system of informal segregation, in which Black Americans were allowed in the Waldorf (and elsewhere), but were certainly not welcome.

Despite this the Waldorf was at the heart of a fundamental shift in American culture which “invited” ordinary Americans access beyond the velvet rope – as long as they could afford it. As James McCarthy and John Rutherford said in their 1931 book, Peacock Alley: “The average man and woman … frowned upon grand display – chiefly because the average person knew it was beyond his or her own horizon of enjoyment. The arrival of the Waldorf, however, was an invitation to the public to taste of this grandeur.”

And it wasn’t just the paying customers. During its 30th anniversary in 1923, the Waldorf elevated its staff – its servants – to the level of guests. Reporters for the Birmingham Age-Herald noted: “Practically the entire staff of the hotel were guests … the affair reached the topnotch of Waldorf democracy, for the waiters and financiers, telephone girls and captains of industry, coat-room clerks and merchant princes sat side by side and swapped reminiscences with each other.” The article continues:

Oscar sat [at] the head of his own table as guest of honor. For a brief time Oscar was no longer the solicitous host … For an hour or two Oscar was himself the guest, and the entire kitchen menage of the Waldorf-Astoria was kept hopping filling his wants and those of his fellow guests.

Library of Congress

But being a guest was a temporary experience.

The “Waldorf democracy” described during this event – of people from every walk of life and status mixing and socialising – was very different to that of the Cleveland entourage. It was not party-political, but institutional.

Democracy meant different things, at different times, within the Waldorf; just like in the broader US. The Waldorf, in turn, began to change, and perhaps even lose its meaning within the US by the time of Obama’s presidency.

Chinese ownership

The Waldorf lost its status as presidential palace in 2014. It was bought for $1.95bn by a Chinese company that was later seized by the Chinese government. Security concerns a year later prompted President Obama to stay at the Lotte New York Palace Hotel instead.

Obama’s choice of where to stay – and where not to stay – was widely discussed in the media. The decision was seen to “break with decades of tradition”. ABC News recognised and portrayed it as the end of an era, bidding “Goodbye to the Waldorf Astoria, welcome to the Lotte New York Palace Hotel”. This new era was also framed in geopolitical terms, for example by the New York Times:

With Chinese spies rummaging through White House emails, President Obama has decided not to risk making their spying any easier: He will break with tradition and abandon the Waldorf Astoria … Mr. Obama and other officials will instead take up residence a few blocks away at the Lotte New York Palace.

The same article also pointed out that “hotels have long represented a weak link in security for travelling officials and others”. In fact, Nikita Khrushchev had once got stuck in an elevator at the Waldorf, and “probably thought it was an attempt to assassinate him”.

Covering up an assassination as an “elevator accident” is probably not what Hilton had in mind when he envisaged his hotels as “a means of combating communism”. On the contrary – as Professor Mairi Maclean, a researcher of business elites, put it – Hilton envisaged hotels as a means of “facilitating world peace through international trade and travel”.

Women’s suffrage

It may not have brought about world peace, but the Waldorf did play a part in certain moments of US history because it was always seen as a key arena to lobby rulers, most notably in 1916. Women’s suffrage in America was still four years away. On one side of the debate (and the Waldorf itself) were two hundred suffragists, occupying the East Room. On the other was Woodrow Wilson, occupying the Presidential Suite.

Tschirky recalled being “appointed diplomatic courier … and delegated to carry the first communiqué of the morning … In the midst of it all I stood my ground, swearing myself an ice cold neutral”.

Though neutral on the question of suffrage, Tschirky was willing to reduce boundaries within the hotel, especially if it was good for business. Even as the hotel was being built, Tschirky remembered that “there was not, in all America, such a thing as a motor car, a radio … Nor were cocktails ever seen in private homes; or divorces tolerated in society; nor did women smoke, or wear dresses above their ankles”.

Then in 1907 a notice was put up in the Waldorf: “Women would be served in the hotel restaurants at any time, with or without male escorts.” Freeland noted Tschirky’s simple confirmation that: “We will serve women. What else can you do in a hotel?”

Shutterstock/Everett Collection

A few years later, discussing women’s right to smoke in the dining rooms, Tschirky said: “We do not regulate the public taste. Public taste does and should regulate us.”

During the Waldorf’s 30th anniversary in 1923, newspapers such as El Imparcial celebrated it as “a civic asset of unique importance. And to its other accolades must be added that of contributing effectively to the progress of feminism. It was a memorable day in the women’s rights movement when The Waldorf Astoria granted female access to the Peacock Alley.”

Nevertheless, even the naming of Peacock Alley – a corridor in the hotel that became an important place of congregation, especially for women – was a recognition of exclusivity. It was where people gathered to parade themselves. As the recollection goes in Tschirky’s memoirs: “The Waldorf Hotel was a triumphant picture of the Best People at their best”.

Trump

With their ostentatious decor and gilded interiors, Trump’s hotels could be seen as the modern incarnation of Peacock Alley.

But the tenets of politeness, respect and decorum that Tschirky set down seem like echoes from another age when compared to a recent AI video showing Trump and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu sitting shirtless at a pool with drinks at an imaginary “Trump Gaza hotel”. The video appears to have been a spoof, but that didn’t stop the president from sharing it on Truth Social, his own social media platform, and Instagram.

Like Hilton (who was immortalised in Mad Men, demanding a Hilton on the moon) hotels have always been a part of Trump’s brand. Trump recalled, in How to Get Rich, that his “first big deal, in 1974, involved the old Commodore Hotel site near Grand Central Station” on 42nd Street.

The former Trump International Hotel in Washington DC, opened in 2016, was described as “the epicenter of the president’s business interests in [the capital]”. It was also “a popular choice for lobbyists and Republican Congress members during Trump’s presidency”.

“The Trump Organization sold the hotel’s lease to CGI in 2022, when the hotel was reflagged as a Waldorf Astoria”, though Trump’s firm is rumoured to be in talks to reacquire it.

Another similarity between Hilton and Trump is their use of hotels as symbols for the nation. Each hotel of Hilton’s was envisaged as a “Little America”, “to show the countries most exposed to communism the other side of the coin”.

In the run up to the 2016 US presidential election, at an opening for the Trump International Hotel, Trump “tried to turn the hotel into a metaphor for America”, according to an editorial in Vox. Trump went on to say:

It had all of the ingredients of greatness, but it had been neglected and left to deteriorate for many many decades … It had the foundation of success. All of the elements were here. Our job is to restore our former glory, honor its heritage, but also imagine a brand new and exciting vision for the future.

Forbes commented that this event “could’ve easily been mistaken for a Trump rally”, for example in his statement that “my theme today is five words: ‘under budget and ahead of schedule’ … We don’t hear those words too often in government – but you will!”

Similarly, in an interview with the New York Post, Trump’s son Eric Trump used familiar Maga rhetoric: “Our family has saved the hotel once. If asked, we would save it again”.

What would Tschirky have made of all this? As a political neutral he would have decried Trump’s frequent hotel plugs during political campaigns. No doubt his behaviour would have seemed crass.

Perhaps this reflects two different eras of hotels and their intended functions. Grand hotels such as the Waldorf were shaped by European colonialism, by immigrants like Tschirky and Boldt. But as historian Annabel Wharton describes, the Hiltons “were constructed not, as in the nineteenth century, to meet an established need, but to create one. They suggest that this pressure was not produced simply by the desire for profit, but from a remarkable political commitment to the system that promoted profit-making”. I think we can read Trump’s hotels, and now his politics, in the same way.

The hotel spirit has entered a new phase with Trump’s proposals to “own, level, and develop” the Gaza Strip and create a “Riviera of the Middle East” – riding roughshod over the democratic will of Palestinians in Gaza who dismissed Trump’s vision.

Less than two decades after opening, Tschirky remarked that “many of the great events, financial, diplomatic, political, had had their inception within [the Waldorf’s] stone walls”. For him, it was “an international crossroad where men from all lands came to exchange goods and ideas” and to plan the changes in the world which he would later see come to pass.

Tschirky saw hotels as the most democratic places on Earth. But the “hotel spirit” he espoused – that uniquely American narrative within which he “became a citizen almost overnight” (a feat that seems vanishingly unlikely today) – seems to have been consigned to the past.

“I know that better times will come again”, he says in the preface to his book, “but in terms of the past, I think I have seen the best. New York has changed. America has changed.”

For you: more from our Insights series:

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.