With the 78th Cannes International Film Festival underway this week, there is little doubt that one topic will be central to conversations among filmmakers, sales agents and journalists: United States President Donald Trump’s threat to impose a 100 per cent tax on foreign-made films.

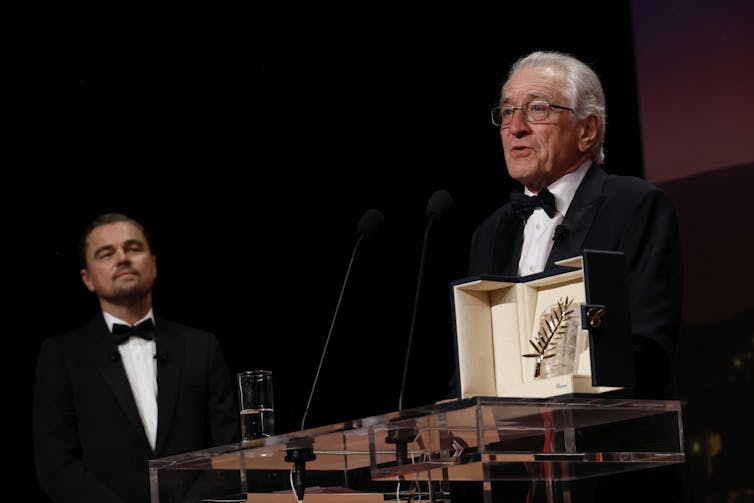

On the opening night, Hollywood icon, Robert De Niro set the tone as he accepted his honorary Palme d’Or award. He used his podium to critique Trump’s actions in the arts, especially Trump’s proposal to tax foreign-made films. He said: “…art is the crucible that brings people together…. Art looks for truth. Art embraces diversity. That’s why art is a threat.” He also added: “you can’t put a price on connectivity.”

Amid an ongoing tariff war, Trump’s proposal — which may ultimately remain an empty threat — goes beyond economic protectionism. It is cultural protectionism. It also reflects language ideologies that have long constrained the American film industry and American engagement with multilingual cinema.

Experts have offered various theories about the motivations behind this threat, as well as why it may ultimately prove unwise. In the rush to brace for impact, we often forget the values behind these extreme positions aren’t new. More importantly, we must also remember why it’s vital to protect these cultural expressions.

As a linguist, I see a clear connection between this proposal and one of the administration’s actions earlier this year, when Trump signed an executive order designating English as the country’s sole official language. This move reflected a deeply rooted monolingual ideology that has long influenced both the U.S. language policy and education systems.

(Photo by Joel C Ryan/Invision/AP)

Monolingual ideology

Such language ideology reflects a belief in the superiority of monolingualism, a view that American linguist Rosina Lippi-Green links to the “myth of Standard American English.”

This myth is grounded in the subordination by one dialect, believed to be of higher quality and status, over other languages and dialects. According to Lippi-Green, the enforcement of this ideology follows a systematic process: language is mystified, authority is claimed and a series of negative consequences ensue. Misinformation is generated, targeted languages are trivialized, non-conformers are vilified or marginalized and threats are made.

Such authority and threats are recognizable in this most recent threat to make access to foreign films difficult. The issue is not just about the economic dimension of foreign-made films. It is also about the perceived threat posed by the presence and influence of other languages. At its core, this reflects a fear or rejection of linguistic diversity.

In the film industry, this monolingual ideology is closely tied to glottophobic attitudes, also referred to by some scholars as linguicism. These terms define the misrepresentation and negative stereotyping of speakers of languages other than English.

Hollywood, in particular, has a long history of portraying foreign or heritage languages in stereotypical and often derogatory ways. Consider, for instance, the German-speaking characters in Second World War films, or more recent depictions of Arabic, Mexican Spanish or Russian speakers.

These portrayals illustrate a tendency to depict other languages as menacing — a point that was also made in the American president’s claim that foreign films pose a “threat” because they constitute “messaging and propaganda.”

Netflix

Linguistic stereotyping

It’s not just characters who speak other languages who have been misrepresented in American films. Those who speak English as a second language — that is with an accent or with a syntax that is marked by their first language — were often played by white actors and subject to similar derogatory stereotypes.

Linguists have identified patterns in these linguistic representations, referring to them as Injun English, Mock Spanish or yellow voices, among others.

Lippi-Green has famously argued that such linguistic depictions are ways to reinforce standard language ideologies through linguistic stereotyping in media, including popular Disney cartoons. They effectively teach American children how to discriminate.

In my work, I examined French-accented English to demonstrate that these representations reflect broader cultural anxieties. Ultimately, this rhetoric reveals more about the U.S. relationship with linguistic diversity than it does about the communities being portrayed.

Trump has made reference to “any and all movies coming into our country that are produced in foreign lands.” But it remains unclear how such measures would impact streaming platforms and the diverse range of films they currently offer.

Hollywood has come a long way since the heydays of linguicism, gradually embracing a more inclusive and multilingual cinematic landscape. Today, films that present a more diverse linguistic landscape are increasingly common. And audiences are accustomed to having access to a wide selection of international content.

The global success of the French series Call My Agent is just one example. Among others are popular French spy thrillers and romances, Swedish thrillers, Japanese anime and Korean dystopian series.

Read more:

Trump’s English language order upends America’s long multilingual history

The pleasure of watching foreign films

For years, foreign language films have been recognized as an invaluable resource for language learning. This fact is supported by language learning apps that increasingly recommend users to view TV programs or movies to support learning. Movies and TV provide access to a variety of dialects as well as authentic forms of language.

As a professor of French media and linguistics, I often use films to teach students about French language and culture. But beyond their educational benefits, foreign-language films offer unique esthetic and emotional pleasures.

Watching a film is to engage with sound and image. The language itself enhances the immersive experience, contributing to the authenticity of the storytelling. For example, one of my students told me he enjoys turning on closed captions in French. These are also known as SDH: Subtitles for the Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing. He does this not just for the dialogue but because they capture the full cinematic experience, including the naming of sounds.

Restricting access to these cultural products would trap viewers in an ideological echo chamber, where only one language is heard and validated.

Fictional representations play a powerful role in shaping and reinforcing real-world attitudes. Monolingual representations potentially foster linguistic discrimination and intolerance toward any word uttered with an accent or in another language. In short, such restrictions could pave the way for a partial and stunted society.