In the past year, leaders of Alberta’s main separatist organization have travelled repeatedly to Washington, D.C., for quiet meetings with senior American government officials in the Treasury and State departments. They’ve reportedly discussed everything from adopting the American dollar to building an independent Alberta military.

These highly unusual interactions — which prompted Canada to warn the Donald Trump administration to respect Canadian sovereignty — are unfolding just as a new Angus Reid poll shows 29 per cent of Albertans would vote, or are inclined to vote, for separation if a referendum were held today.

This is a clear minority, but it’s also an indication of some discontentment. The more interesting question is why a province that has long been among Canada’s richest feels so hard done by that some are willing to contemplate breaking up the country.

Read more:

What if Alberta really did vote to separate?

Alberta defies the usual template

Andrés Rodríguez‑Pose, a professor of economic geography at the London School of Economics, argues that populist eruptions are rooted in regions suffering persistent economic decline, demographic loss and a pervasive sense that they have been “left behind” in a globalized economy.

In Europe and the United States, voters in deindustrialized regions have used the ballot box to punish political leaders for abandoning them. The core grievance is material and territorial: my region is poorer, ignored and slipping further behind.

Alberta does not fit that template.

Its economy has grown faster than any other province since 1950, and it still sits near the top of Canada’s income and employment league tables, even after oil price shocks.

In fact, a central anomaly of Canadian federalism is that Alberta’s economic heft far exceeds its population and representation in Ottawa, feeding a sense of under‑recognized importance rather than marginality.

Alberta is not a place that “doesn’t matter” economically; the anger of those who want to separate stems from believing it matters a great deal and is nonetheless disrespected.

A long history of grievance politics

To understand today’s sovereigntist turn, we need to situate it in Alberta’s political culture. For nearly a century, Alberta political leaders have fused populism, “western alienation” and oil politics into a powerful narrative about Ottawa exploiting the province’s resources.

From Social Credit premiers William Aberhart and Ernest Manning through to Progressive Conservative Peter Lougheed, provincial governments portrayed hard‑working Albertans as besieged by federal political leaders and eastern “money powers” siphoning off “their” oil wealth.

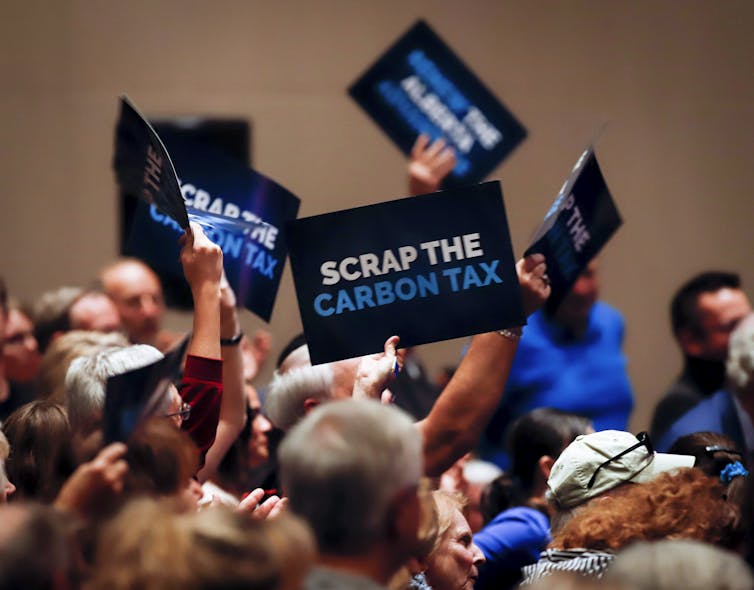

That story hardened during the National Energy Program in the 1980s and was revived against former prime minister Justin Trudeau’s climate policies and carbon pricing, which UCP governments portrayed as an attack on a fossil‑fuel‑based way of life.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jeff McIntosh

Recent scholarship shows how this individualism, free‑market ideology and fossil‑fuel identity has been continually updated through the Reform Party, the “firewall” letter, Jason Kenney’s “Fair Deal Panel” and, most recently, Premier Danielle Smith’s Alberta Sovereignty Within a United Canada Act.

Alberta’s sovereigntist politics are therefore less an aberration than a radicalization of longstanding themes: populist anti‑elite rhetoric, resentment of Ottawa and a deep attachment to oil and gas.

The Alberta Prosperity Project

The Alberta Prosperity Project (APP) crystallizes this paradox. Its leaders speak the language of hardship and urgency — “we see the writing on the wall” — and claim Alberta must seize “freedom, prosperity and sovereignty” from a confederation that no longer shares its “values” and “entrepreneurship.”

Their draft fiscal blueprint, The Value of Freedom, promises that independence would unleash tens of billions in savings, eliminate personal income tax, slash other taxes and transform Alberta into “the most prosperous country in the world.”

Central to this case is the complaint that Albertans pay too much to Ottawa and get too little back in return — especially through equalization and other transfers. In this telling, sovereignty — or at least a radically “restructured” relationship with Canada — is the only way to stop Ottawa from siphoning off the fruits of Alberta’s oil.

Yet this narrative glosses over Alberta’s own choices. During boom years, successive Conservative governments — strongly backed by many of the same constituencies now drawn to sovereigntist rhetoric — cut taxes, kept royalties comparatively low and resisted building a large, Norway‑style savings fund.

Read more:

Alberta budget means Albertans are trapped on a relentless fiscal rollercoaster ride

At the same time, Alberta chronically under-invested in health care, education and social services relative to its fiscal capacity, leaving systems stretched even before the COVID-19 pandemic. When oil prices fell, the result was not simply federal neglect but the exposure of a model that had privileged low taxes and immediate consumption over long‑term resilience.

In other words, the Alberta Prosperity Project is right that Albertans feel squeezed — but its account of who did the squeezing is selective. Sovereigntists who blame Ottawa and equalization for every shortfall ignore the role of provincial policy in creating the ongoing boom-and-bust cycle in Alberta.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jason Franson

‘Fossilized’ regionalism

Another source of discontent lies in the collision between Alberta’s oil‑dependent economy and the global climate transition.

Scholars say Alberta regionalism is “fossilized” — decades of political and economic investment in oil and gas have locked in expectations about jobs, identity and provincial autonomy.

As federal and international climate policies intensify, many Albertans interpret decarbonization as a threat. In a 2023 poll, three in five Albertans said they believe the province is right to resist the federal government’s net-zero goals.

The fear is not that Alberta has been excluded from growth, but that it will be deliberately left behind in the next economy while its existing wealth is constrained or stranded.

The Alberta Prosperity Project’s fiscal plan doubles down on hydrocarbons, promising prosperity through continued or expanded oil and gas development while railing against “externally imposed limits” on emissions.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jeff McIntosh

Idiosyncrasies

The Alberta Prosperity Project embodies the idiosyncrasies of this approach. It calls for an independent, low‑tax petro‑state, denounces federal redistribution and promises world‑leading prosperity. Yet it rarely acknowledges that the same political camp has historically opposed higher royalties, stronger stabilization funds and robust social investment when times were good.

It presents the climate transition as an illegitimate imposition rather than a predictable structural shift that responsible governments could have prepared for.

Recent revelations that APP leaders have been workshopping state‑building with senior U.S. officials shows this isn’t just a symbolic protest, but an attempt to secure external backing for an oil‑centred future that Canada’s constitutional order and climate obligations cannot sustain.

Alberta’s sovereigntist discontent is a three-way collision: long‑cultivated politics of grievance against Ottawa; a self‑inflicted fiscal and social vulnerability rooted in decisions made during boom years; and a global energy transition that threatens a deeply embedded regional identity.

The danger? In insisting on a future of perpetual oil‑funded prosperity while railing against transfers and federal authority, movements like APP offer Albertans a superficially compelling story that cannot be reconciled with either Canada’s Constitution or the realities of a warming world.